By Thomas M. Cooper

The Cleveland Civil War Roundtable

Copyright © 2024, All Rights Reserved

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in The Charger in December 2024.

The biographical details of our ancestors emerge slowly, and perhaps this is a good thing. History needs to marinate some events over time so that their meaning can be understood by the living, in deeper, broader contexts. This is especially true for wartime histories involving trauma and the years required to remember-and-resolve. This is one of the reasons we study these periods and come together to talk about them.

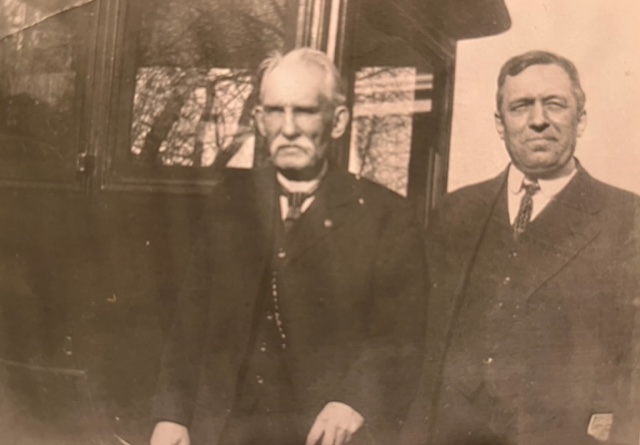

My family has carried around images and stories of “Blind Grandpa Cooper” for several generations, and we have over the decades carefully maintained photos of him and some of his belongings. My grandmother remembered him well, things he said and did, and told me about him many years ago. I have personally been aware for 60 years of his Civil War service, engagements, capture at Chickamauga, imprisonment at Richmond’s Belle Isle, Libby, and Castle Thunder prisons, in Danville, and release. But in spite of hours of searching and reflecting on this family history, the “real story” did not emerge until four years ago, and with the help of a few others, mysteries fell open rapidly in succession, in a domino-like effect.

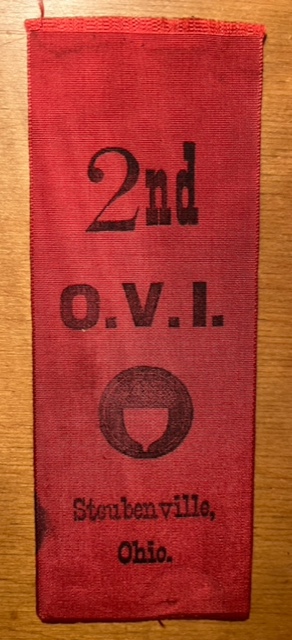

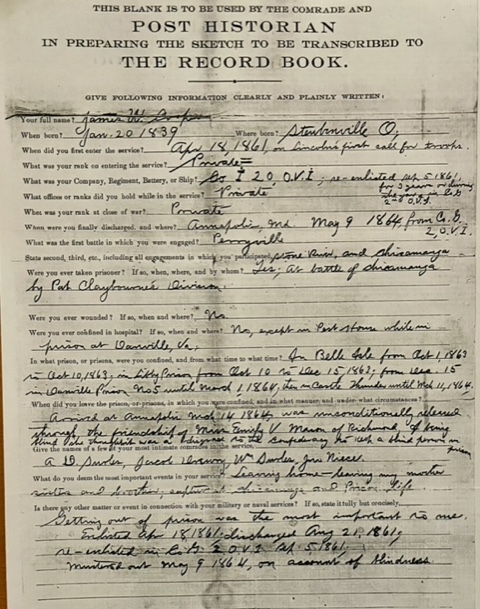

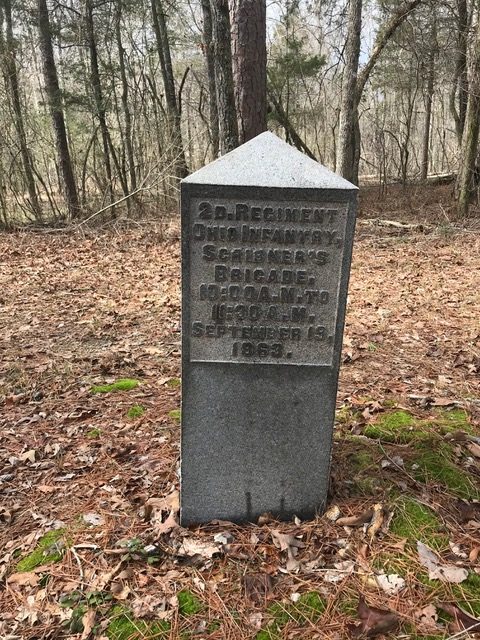

James W. Cooper, a 22-year-old plasterer in Steubenville, Ohio, responded to Lincoln’s first call for troops in April 1861, serving several months in the 20th OVI, then re-enlisting on September 5, 1861 as a private with the 2nd OVI, on active status until his discharge due to blindness on May 9, 1864, and return home with accompaniment to Steubenville. His Company G was engaged at Perryville and Stones River before Chickamauga. On September 19, 1863 his 2nd Ohio and adjacent units, including the 33rd OVI, were driven back through the woods at Winfrey Field at Chickamauga by Patrick Cleburne’s division. Cooper was taken prisoner, moved as a POW to Richmond and then to the brick tobacco warehouses of Danville, which had been repurposed to house hundreds of Union prisoners, packed into small rooms. There he contracted smallpox, with lesions in his eyes leaving him permanently blind. In his Post Historian’s interview, Cooper’s words read: “Arrived at Annapolis, MD Mar 14, 1864, was unconditionally released through the friendship of Miss Emily V. Mason of Richmond. I being blind she thought it a disgrace to the Confederacy to keep a blind person in prison.”

In reply to the last question, which asked Cooper to state any other matter or event in connection with his military service, Cooper answered, “Getting out of prison was the most important to me…Mustered out on May 9, 1864, on account of blindness.”

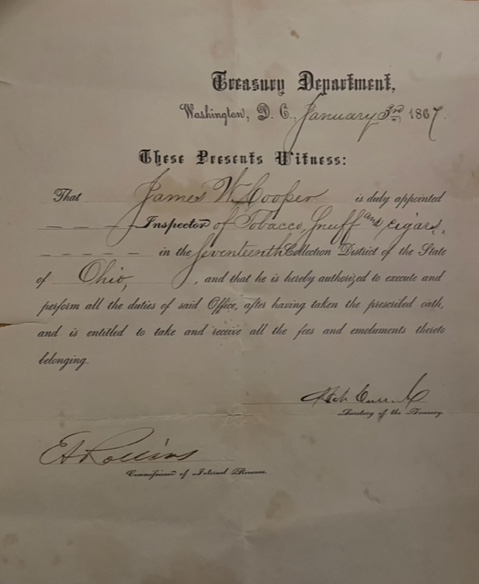

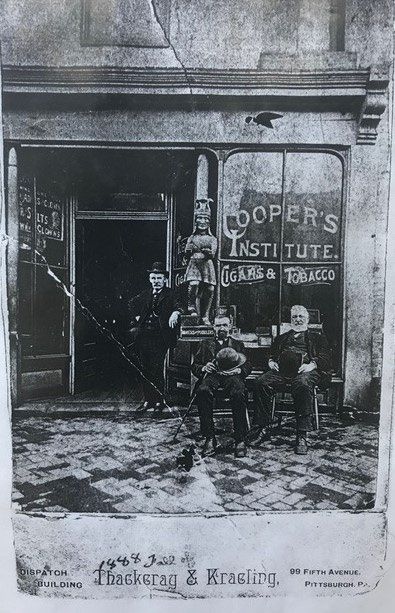

Post-war life in Steubenville saw Cooper run a tobacco store (“Cooper’s Institute”), a popular gathering place for veterans, and he was appointed in 1867 as the “Inspector of Tobacco, Snuff and Cigars in the Seventeenth Collection District” in Ohio by Lincoln’s Treasury Secretary, Hugh McCulloch. Cooper married, had one surviving child, later moving to Newark, Ohio (my hometown) with his son, where he died, with burial in Atwater, Ohio, his wife’s hometown. His father, William Lewis Cooper, served in the 25th OVI, was wounded, and was buried in 1874 in Steubenville’s Union Cemetery next to the 1869 Civil War monument dedicated to and with the inscription “The Great War for the Suppression of the Rebellion.” Brother Justin M. Cooper served as a 16-year-old in the 129th OVI and moved to Kansas after the war. All this was known by the family through documents passed down and via military files obtained through the National Archives.

The document authorized Cooper “to execute and perform all the duties of said Office” (whatever those duties entailed).

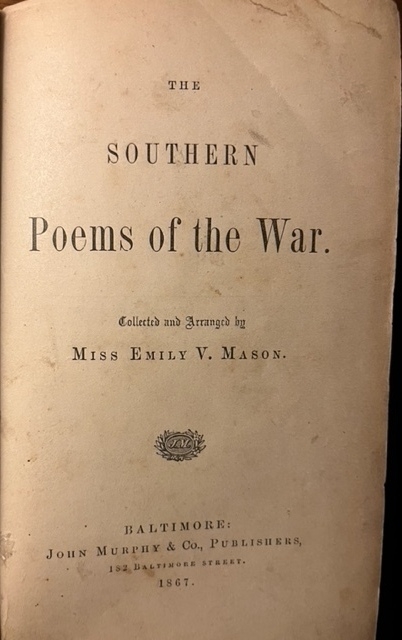

But who was this Miss Emily Mason in 1864? Just a name. Where would there be sources of information about a young private citizen of Richmond? Nearly 60 years passed, and then in 2020 my Dartmouth College classmate Joseph Cosco, a recently retired American Studies and English professor, moved to Richmond and offered to “look up” Emily Mason. At that point there was little information about her on the internet. (Now she is much more “discoverable.”) But the Library of Virginia boasted large oil portraits of her and her brother Stevens T. Mason, who was the first governor of Michigan, descended from the distinguished colonial Mason family of Virginia which includes George Mason, one of the Founding Fathers. Emily Mason had edited or authored two books: Southern Poems of the War (1867) and Popular Life of Gen. Robert Edward Lee (1872). She had been an intimate of Mrs. Lee.

I quickly traveled to Richmond to meet with the Library of Virginia’s Meghan Townes and to see the prison sites, walk across the James River, hike around Belle Isle, and begin to dig deeper into more obscure archives. Quite out of the blue (it seemed) an eBay post popped up in my inbox from Defunct Bookstore of Nashville offering an original copy of Southern Poems of the War by Emily V. Mason. I bought it for $50. Two strong impressions emerge from that barely postwar compilation – the mournful expressions about the loss of the young men of the South, the hardships left to families, plus the compassionate resolve for all young soldiers, which bore evidence in the care provided to the young men of the North by Miss Mason and many other women, whose relief and nursing work has now been studied and documented. Mason was a matron in Richmond hospitals, taking up the cause of the wounded and prisoners on both sides and leader among the women in Richmond who advocated for more humane conditions. To be noted, however, is the absence of any mention of slavery, Black soldiers, or Black prisoners.

Cooper said in his Post Historian’s interview that this was one of the buildings where he was held. The surviving, adjacent warehouse is from the same era.

Among other narratives, see a 1998 academic thesis by Elise Allison, “Confederate matrons: women who served in Virginia Civil War hospitals” or the fruit of several hours of my library spadework – Emily Mason’s 1902 article in The Atlantic Monthly, “Memories of a Hospital Matron” (Part One and Part Two) in which she wrote: “And my poor, ugly smallpox men! How could I fail to mention you, in whose suffering was no ‘glory,’ – whose malady was so disgusting and so contagious as to shut you out from companionship and sympathy! … Often in the night I would wake, thinking I heard their groans. Lantern in hand, and carrying a basket of something nice to eat, and a cooling salve for the blinded eyes and the sore and bleeding faces, I would betake me to the tents to hear the grateful welcome. ‘We knew you would come tonight. Can I have a drop of milk or wine?’ A few encouraging words and a little prayer soon soothed them to sleep. These were my favorites.” Sitting in that library, a 150-year window of time swung open, in a very personal way.

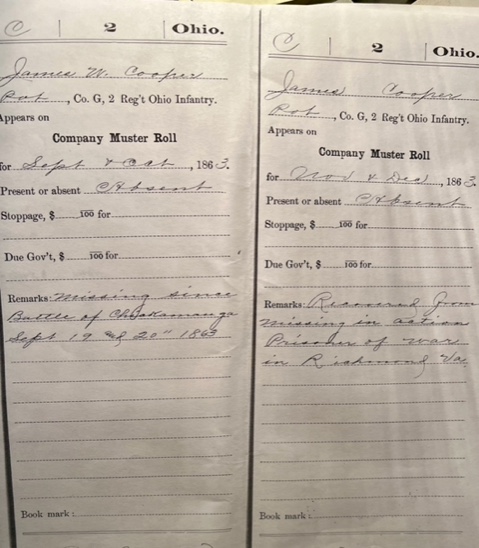

The card on the left lists Cooper as “Missing since Battle of Chickamauga.”

The card on the right lists Cooper as “Prisoner of war in Richmond Va.”

Very recently I was in contact with a distant relative I had never met, who found a 1915 obituary of Private James W. Cooper from a Steubenville newspaper. I already had a lengthy Steubenville obituary, but this one provided additional detail that added to the “plot,” excerpted here:

“At the battle of Chickamauga, Mr. Cooper was captured and…was taken seriously ill and removed with a number of companions from the prison to tents, where they were forced to spend the winter. Mr. Cooper contracted a heavy cold and gradually lost his sight. A Miss Mason, who was acting as a field nurse, seeing Mr. Cooper’s condition, appealed to President Jefferson Davis of the Confederate States and was successful in obtaining a parole for him…No man who ever lived in Steubenville had more friends than ‘Jimmy Cooper,’ as he was familiarly called and he was respected by everybody rich and poor…His cigar shop at the corner of Fifth and Market streets was the headquarters for the men about town and whatever was going on in ‘Old Steuby’ was sure to be discussed there.”

Shortly before the pandemic made travel impossible in 2020, I arranged a phone call with my lifelong friend and Civil War expert Jim Hall of Mt. Vernon, Ohio, who dropped everything to help me research the 2nd Ohio’s location and engagement in the field on September 18-19, 1863 and the narratives of the day. A visit to Chickamauga soon happened. I made contact with Chickamauga National Military Park Historian Jim Ogden, arguably the foremost expert on that engagement. With Jim’s unselfish time and advice, I walked the 2nd OVI’s movements of September 19, but more importantly we began to flesh out the narrative of the forced path of the prisoners through Confederate lines, as they were marched through Ringgold, Tunnel Hill, and Dalton, Georgia where they were loaded onto boxcars. After a week or more of rail transit through Atlanta and North Carolina, they arrived in Richmond where they were moved into outdoor camps. Jim Ogden was uncertain about the particulars of that journey, but suggested I consult Lois Lambert’s 2008 excellent history of the 33rd OVI, which fought adjacent to the 2nd Ohio at Chickamauga in Scribner’s Brigade. This volume cited the published diary of Private Warren Johnson (who was captured the same day as Cooper) and his undated “Life in Confederate Prisons, Account from Unidentified Newspaper.”

Fortuitously, my nephew Matthew Cooper, an Ohio State University Law School professor and authority on library research and reference services, was intrigued by the search, jumped on board, and knew where to look, first finding the “New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center’s 1868 Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of Military Statistics,” which led to Private Johnson’s first-person, remarkably detailed account (of his capture, POW march, train transport, and arrival at Belle Isle) in an obscure, microfilmed 1868 Scioto County, Ohio newspaper. Johnson arrived at Belle Isle on the same day as my ancestor, and then was sent to Danville just three days before. In his account, Johnson mentions the smallpox patients at Danville. We conveyed the scanned newspaper account to Jim Ogden, and it has now been added to the National Military Park’s archive for the 33rd Ohio. During this entire process – all opening up in about a two-month period – Jim also shared a rare printed account of the capture at Chickamauga of another 2nd Ohio soldier, Horace Abbott, and Abbott’s 1889 “My Escape from Belle Isle” narrative describing a parallel experience of capture, transport on the same routes, meager rations, dialogue with guards, and conditions of captivity. In all, this was truly an immersive experience for this descendant, grateful for the timely (and uncanny!) connections with experienced friends, family, and professional researchers, who were all too willing to help bring the past to life.

Author’s note: A superb regimental history of the 2nd Ohio is Richard Baumgartner’s 2011 The Bully Boys: In Camp and Combat with the 2nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment 1861-1864. Among the regiment’s alumni are James Andrews of Andrews Raiders and the Great Locomotive Chase of April 12, 1864. Blue Acorn Press, 2011.

See also: Heroes of the Western Theater: 33rd Ohio Veteran Volunteer Infantry. Little Miami Publishing, 2008.

Click on the book links on this page to purchase from Amazon. Part of the proceeds from any book purchased from Amazon through the CCWRT website is returned to the CCWRT to support its education and preservation programs.