By David A. Carrino

The Cleveland Civil War Roundtable

Copyright © 2016, All Rights Reserved

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in The Charger in October 2016.

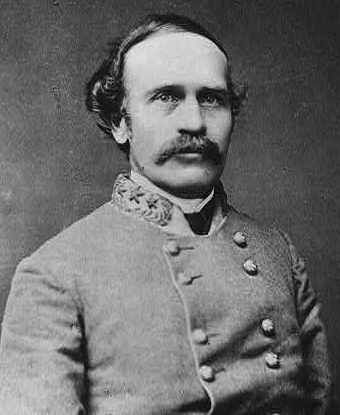

The Civil War is occasionally referred to as the North vs. the South. However, people who are knowledgeable about the Civil War know that that is not entirely correct on an individual level. This is because quite a few of the combatants were from the opposite part of the country, but felt loyalty to the other side and chose to fight on that side. One such person is General Bushrod R. Johnson, who was a Northerner by birth, but who fought for the Confederacy. Ironically, just like Johnson’s life had a geographic dichotomy across the Civil War’s sectional divide, Johnson has two final resting places with a similar geographic duality, one in the North and one in the South.

Although Johnson fought for the Confederacy, he was born in Ohio and, moreover, grew up in a family that had abolitionist sentiments. After graduating from the U.S. Military Academy and serving in the Mexican-American War, Johnson obtained a position as an instructor at the Western Military Institute in Georgetown, Kentucky. A year afterward, he married Mary Hatch, and the couple later had a son, Charles, who was their only child. Charles was physically and mentally handicapped and remained an invalid his entire life. Eventually Johnson’s position as an instructor necessitated a move to Nashville, Tennessee, where Mary died, leaving Johnson to care for their handicapped son. By the time of the outbreak of the Civil War, Johnson had become a prominent resident of Nashville, which caused him to side with the Confederacy, and he served in the Confederate army for the entire war. (A more detailed description of Johnson’s life and Civil War service can be found in the history brief The Best Confederate General from the Buckeye State.)

One interesting anecdote about Bushrod Johnson is that he has two final resting places. It is certainly not unheard of that men who fought in the Civil War were later reinterred from their initial place of burial. But the story of Bushrod Johnson’s reinterment is interesting, because it was 95 years before his remains were moved over 300 miles to lie beside his wife. In addition, this would not have happened without the insight and efforts of a descendant of a Confederate soldier who took action after a serendipitous remark. According to an account that was published in the August 7, 1975 edition of the St. Petersburg (Florida) Evening Independent, a person named Noble Wyatt deserves the credit for Bushrod Johnson finding his way home after being interred for almost a century in enemy territory. Wyatt’s motivation for bringing about Johnson’s reinterment may have come from his interest in the Civil War and also because his maternal great-grandfather served in the Confederate infantry.

Although Bushrod Johnson lived for many years in Nashville prior to the Civil War, he moved north to Miles Station, Illinois with his handicapped son ten years after the war. Different explanations can be found for why Johnson chose to move to that location, but his reasons for moving were his deteriorating financial situation and his declining health. Johnson died of a stroke in 1880, and Wyatt stated that Johnson “lay unconscious for several weeks before he died.” Johnson’s wife, Mary, who had died in 1858, was interred in Nashville, but Johnson’s friends in Miles Station likely did not know that Johnson had purchased a burial plot for himself in the Nashville cemetery in which his wife was buried, nor could Johnson’s handicapped son tell this to them. Whatever the reason for the decision not to return Johnson’s body to Nashville, Johnson was buried in a cemetery in Miles Station and remained there until a chance comment many decades later.

This marker was placed on the grave where Johnson was originally buried.

Noble Wyatt, the person who initiated Johnson’s reinterment, was born in Charleston, West Virginia and eventually, for work-related reasons, lived in Alton, Illinois, which is less than 20 miles south of Miles Station. Wyatt stated that a woman named Chloris Yost, who lived in Alton, told him about the Confederate general’s grave. Wyatt’s description of Johnson’s grave is that it was “obscure” and also neglected, as evidenced by the tombstone being broken. Wyatt further stated about Johnson’s grave that “there was no reference to the Confederate Army on his tombstone.” Because Wyatt knew that Johnson’s wife is buried in Nashville and that Johnson considered Nashville his home, Wyatt sought to have Johnson’s remains moved to Nashville. Wyatt obtained permission from Johnson’s three closest living relatives to have the general’s remains moved.

On August 2, 1975 Johnson was exhumed from his Miles Station grave, and on August 23, 1975 Johnson was reinterred in Nashville. A marker was placed on Johnson’s Miles Station grave to indicate that Johnson had been buried there, and this marker notes his Confederate service and his reinterment in Nashville. For spearheading the return of Bushrod Johnson to Nashville, Noble Wyatt received an award. Thanks to Noble Wyatt’s Civil War astuteness and his willingness to take action, Ohio-born Confederate General Bushrod Johnson, who spent many years away from Mary, was reunited with his wife and his home, where he could at long last rest in peace.

Related link:

The Best Confederate General from the Buckeye State

A number of sources were used for this article. The most useful sources are as follows.

Bushrod Johnson Will Be Reburied ‘With Dignity,’ St. Petersburg (Florida) Evening Independent, Number 238, August 7, 1975

Former Enemies Who Became Friends by John J. Dunphy, Medium: Human Stories and Ideas, September 30, 2022

Macoupin Abolitionist Became Confederate General by John J. Dunphy, The Telegraph, September 9, 2022

Major General Bushrod Rust Johnson, CSA by Janet Greentree, Stone Wall (The Newsletter of the Bull Run Civil War Round Table), volume XXXI, issue 10, pages 15-23, October 2024

Bushrod Johnson: Yankee Quaker, Confederate General by Roy Morris Jr., Warfare History Network, Winter 2017