By Daniel J. Ursu, Roundtable Historian

The Cleveland Civil War Roundtable

Copyright © 2025-2026, All Rights Reserved

Editor’s note: This article was the history brief for the October 2025 meeting of the Cleveland Civil War Roundtable.

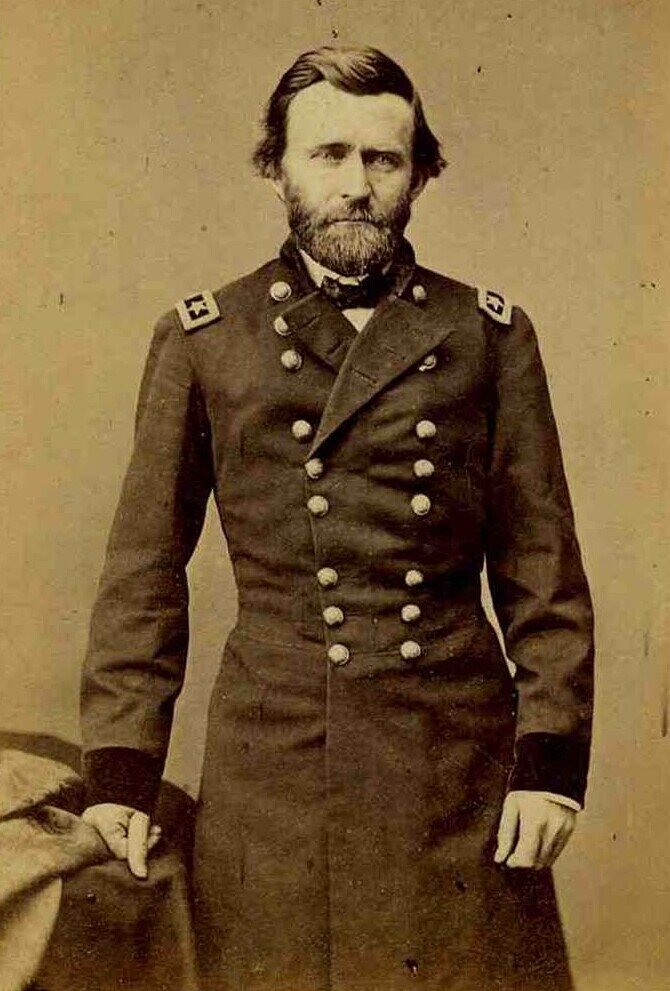

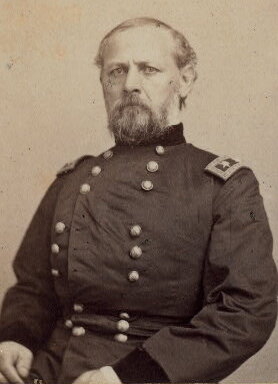

We just returned from a wonderful field trip to Vicksburg, where we studied General Ulysses S. Grant’s campaign to capture the South’s “Gibraltar of the West.” It was a combined arms operation that included both the Union army and its brown water navy. Grant had employed such tactics previously and arguably under more difficult circumstances at the Battle of Shiloh, where General Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio arrived after being shuttled across the Tennessee River – during the battle, at night in a rainstorm. In Wiley Sword’s book Shiloh: Bloody April, Buell is quoted as saying that it was “A brilliant page in History.” The daunting challenges of using transport ships to move troops and supplies during the Civil War are mentioned in most accounts only in passing. As such, this history brief focuses on part of the multitude of components that made up the logistics of crossing the Army of the Ohio over the Tennessee River, which must have appeared to onlookers to be an assemblage of organized chaos.

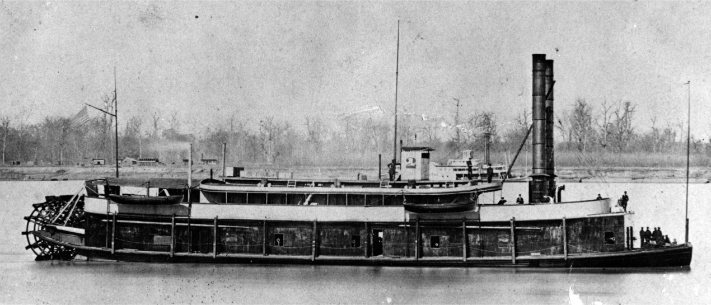

General Grant was born in Ohio and spent his formative years near the Ohio River, subconsciously gaining the skill set required to manage riverine operations that seemed to come naturally to him. The steamboats he used were not ships of war, but rather contracted civilian vessels. River steamboats at the time of the Civil War were made of wood with shallow drafts, flat bottom hulls, and flexible drive trains to help “bend” their hulls over the snags and sandbars found in the Western Theater rivers. Most relied on deck space to stack cargo with relatively minimal holds below deck. Accordingly, they were top-heavy and required skilled pilots.

The average river steamboat could carry 650 tons of bulk cargo at nine knots. Sidewheel boats were most popular until the 1850s when sternwheelers began to emerge. Sternwheelers had more complex drive linkages, but were more nimble around the river flotsam and drew even less water, which made them more capable in times of drought or in shallow channels. However, sidewheelers were more stable and mechanically simpler as well as a bit faster and easier to turn.

To man these vessels, the Union army relied on civilian rivermen who effectively became militiamen. These rivermen had to overcome unpredictable waterways, unsavory merchants, potentially hostile native Americans, bandits, corrupt contractors, and themselves. The rivermen were highly trained with specialized skills, especially the experienced pilots familiar with the ever-changing river channels. The boats had few military personnel aboard, if any. Some boats were family-operated with spouses and children on board, and others were business assets owned by individuals or firms.

On our field trip, we stood at the shore of the Mississippi River and witnessed its treacherous speed and dangerous currents. The Tennessee River at Shiloh had the same, but in a more narrow and less maneuverable channel. Hence, because of the river’s strong and unpredictable currents, most farmers, lacking commercial wealth, loaded their produce onto self-built rafts or flatboats and floated them downstream. Consequently, only a handful of riverboat pilots were familiar with the Tennessee River prior to the Civil War. But because the war disrupted trade, risk-taking steamboat pilots and operators from other rivers were willing to sign contracts to haul troops, ammunition, and supplies.

The steamboats ran on wood and coal. The typical steamboat needed 50 to 70 cords of wood and 3,000 to 4,000 bushels of coal for every 1,000 nautical miles. Most of the coal came from Appalachia and was barged on colliers out of Pennsylvania. Steamboat engines were designed for a mixture of wood and coal, but if needed could run solely on wood. However, they consumed more and produced less heat, which meant less steam pressure and therefore less power. As a side business, farmers cut trees along the rivers and stacked wood on riverbanks in exchange for cash, provisions, or tools. Demand beckoned professional woodcutters transporting inland wood to specially built landings. By the time of the Battle of Shiloh, sporadic combat along the rivers affected this process, so the Union made efforts to pre-position wood and coal on barges along the river banks.

The Tennessee River generally had steep bluffs on both shores. Roads inland had to be cut and maintained to accommodate steamboats. Savannah, on the eastern shore where Grant had his headquarters at the Cherry Mansion, which stands to this day, prospered because it was one of the only flat beaches with a gradual incline upward from the Tennessee River. Also nurturing steamboat activity in the vicinity of Savannah and Pittsburg Landing were a couple of small islands that created areas of slack water, which was valuable for shelter against the river’s strong current.

It is a given that Buell’s Army of the Ohio arrived on the opposite side of the river after a long march from Nashville and crossed just in time to turn the second day into a Union victory. In light of all of the foregoing, the logistical effort by Grant, his staff, and rivermen to move Buell’s army across must have been extremely complicated, but it was mostly undocumented. Sources vary, but most historians conclude that there were about 150 to 200 transport steamers involved during the battle. Viewing the Shiloh landing site preserved by the National Park Service, it must have been very congested, even if there were only 15 or 20 boats in the area. Adding to the congestion, staged offshore were at least three casualty vessels known today as hospital ships. Lastly, it is well known that the USS Tyler and USS Lexington with their heavy guns were churning offshore while suppressing rebel positions on Dill Creek at dusk and through the night.

An average steamboat had space for 600 to 800 men, but at least one other steamer would be needed to carry their ammunition, rations, camp equipment, medical supplies, officer horses, camp followers, and horse forage. Further, a six-gun field artillery battery without horses could fit on one boat, but another two or three were needed for the limbers, caissons, ammunition, forge wagons, gunners’ baggage, and horse forage. Also, the steamers had to be loaded and unloaded. Troops and horses could unload themselves, but baggage, ammunition, rations, and so forth at an unimproved landing such as Pittsburg required time-consuming and backbreaking labor to unload. At the time of the Battle of Shiloh, the river was running high and in the opposite direction that the Union vessels needed to travel. Lastly, this feat was accomplished at night during a rainstorm. But we know for a fact that with Yankee ingenuity, it happened.

In James Lee McDonough’s book Shiloh – in Hell before Night, he recounts the well-known scene of General Ulysses Grant in the rain leaning against a tree while whittling and conversing with General William Sherman, who states, “Well Grant, we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?” to which Grant replies, “Yes, lick ’em tomorrow though.” Grant’s prediction was bold, but the nameless and underappreciated staffs, laborers, and rivermen overcame extreme challenges and in doing so made possible the Army of the Ohio’s remarkable crossing over the Tennessee River during the rainy night. Because of that unheralded effort, by morning Grant would already have 17,000 men of the Army of the Ohio in line for the counterattack. And as history shows, Grant did indeed “Lick ’em tomorrow.”