By Brian D. Kowell

The Cleveland Civil War Roundtable

Copyright © 2024, All Rights Reserved

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in The Charger in October 2024.

No one knows the exact number of women soldiers who served in the American Civil War. Historians DeAnne Blanton and Lauren M. Cook, who chronicled 240 women in uniform in their book They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War, estimate that over 400 served North and South. The American Battlefield Trust estimates that the number could be as high as 700 women who served in uniform. “The full extent of women’s participation as armed combatants in America’s bloodiest and most costly conflict will never be known with certainty,” wrote Blanton and Cook, “because women soldiers fought for the most part in secrecy.” Some followed their husbands or sweethearts off to war, some escaped from domestic abuse or poverty, and others served for patriotic reasons. Many women soldiers hailed from Ohio.1

Mary Smith, a 22-year-old Ohioan, passed herself off as a man and enlisted in the 41st Ohio Volunteer Infantry. She joined not only for patriotic reasons, but to avenge the death of her only brother at Bull Run. She was sent to Camp Wood in Cleveland, where she was described as “intelligent and good looking.” She was soon suspected of being a woman due to her mannerisms as well as her ability to sew like a skilled professional. Her true gender was soon discovered, and her soldiering career came to a swift end.2

Having a distinctly female manner also gave away another disguised soldier in the 3rd Ohio Infantry. The young lady enlisted with her brother at Camp Jackson in Columbus, Ohio. They were both sent with the regiment to Camp Dennison for training. The two became separated, and thinking her brother had been transferred to Pennsylvania, she went to her commanding officer to request a transfer there as well. In a remarkably soft voice she pleaded her case. The colonel, scanning her closely, said, “Young man, you are a woman.” Soon tears burst from her eyes, and she was discharged from the army.3

The 10th Ohio Cavalry was organized in Cleveland at Camp Taylor in October 1862. In February 1863, four months after enlisting, a woman soldier was discovered in their camp. When she was interviewed, she gave her name as Henrietta Spencer from Oberlin, Ohio and said that she enlisted to avenge the death of her father and brother at Murfreesboro. Unfortunately for her, she was quickly sent packing for Oberlin.4

The 59th Ohio Volunteer Infantry was organized at Camp Ammen in Ripley, Ohio, and was led by Colonel James P. Fyffe, part of General Buell’s Army of the Ohio. They fought at Shiloh under Buell and then at Stones River and at Chickamauga under General Rosecrans. The 59th was at Chattanooga and fought with Sherman’s army to Atlanta until it was mustered out on October 31, 1864. Reportedly two unnamed women served in the 59th Ohio Volunteer Infantry.5

Catherine Davidson fought with the 28th Ohio Infantry at Antietam. The 28th Ohio was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Gottfried Becker and was part of Colonel George Crook’s brigade in the IX Army Corps. The 28th Ohio was engaged along Antietam Creek, adjacent to the Lower Bridge, facing the 20th Georgia Infantry. Once the bridge was crossed by other troops, the 28th Ohio forded the creek and moved forward to the Lower Bridge Road, facing Drayton’s and Kemper’s brigades of D.R. Jones’ division. The regiment lost 42 men, killed or wounded. One of those wounded was Catherin Davidson, who suffered a terrible wound to her right arm.

Shortly after the battle, the Governor of Pennsylvania, Andrew Curtin, arrived on the field to help with the wounded. Davidson was one of the soldiers he consoled, and he helped her into an ambulance. Davidson, thinking she was dying, gave Curtin her ring as a token of thanks. Army surgeons amputated Davidson’s right arm between the shoulder and the elbow. Her secret was discovered on the operating table. She survived the wound but was dismissed from the army.

After her recovery, Davidson was in Philadelphia and called upon Governor Curtin, who happened to be in the city at the Continental Hotel. Recognizing the governor, she rushed over to him, kissed him on the forehead, and poured out her thanks for his kindness to her. Catherine explained who she was and how they had previously met. She also reminded him that she had given him her ring on the battlefield. Curtin was stunned that the soldier he helped was a woman. He was wearing the ring, and Davidson showed him her initials etched on the inside of the band. Governor Curtin offered the ring back, but Catherine wanted him to keep it, saying, “The finger that used to wear that ring will never wear it anymore. The hand is dead, but the soldier still lives.”6

There is a remarkable story in the Cleveland Leader titled “Romance of an Ohio Woman” about William Lindley and his wife Martha Parks Lindley. William decided to join the 6th U.S. Cavalry Regiment in 1861, and his wife Martha was determined to go with him. After entrusting her two children to the care of her sister, she enlisted as Private Jim Smith along with William. Once sworn in, her husband pleaded with her to go home, but she insisted on staying in the army. “I was frightened half to death,” she admitted, “but I was so anxious to be with my husband that I resolved to see the thing through [even] if it killed me.”

In late 1861, Martha was promoted to sergeant but was later demoted. This happened again in the fall of 1862, when she was again promoted to sergeant only to be later demoted in rank. The cause for these demotions remains unclear, but Martha faithfully served beside her husband for three years. She did spend ten months of her enlistment detached on hospital duty as an orderly for the regimental surgeon. In the 1864 election, as Jim Smith, she was allowed to cast a ballot for Abraham Lincoln for president – the first and last vote of her life since women could not legally vote until 1919. In August 1864, upon the expiration of their terms of enlistment, Martha and William were mustered out of service. Through all that time, no one knew that Private Jim Smith was a woman.

When William decided to reenlist in the 6th Ohio Cavalry, Martha said she’d had enough of war and went home. She retrieved her two children and waited for her husband’s return. The couple was reunited in July 1865 and settled in Cleveland. Martha gave birth to two more children after the war. She was too busy raising her children after the war to speak publicly about her time in the army. “The fact that she served throughout the war is known to but a few of her friends and acquaintances,” according to the Cleveland Leader. The couple apparently also shared their war stories with their children. To her family she was as much a hero as her husband. William Lindley died on July 3, 1899, and Martha passed away ten years later on December 15, 1909 at the age of 74. It was 30 years after the war when one of her children brought Martha’s story to the public. The children had carefully saved their mother’s uniform and pistol and handed them down from generation to generation.7

Many women followed their spouse, lover, or relative to war. An Ohio woman, using the alias Private Joseph Davidson, followed her father into war. They fought side by side at Chickamauga, where her father was killed in the battle. Her real name and unit are lost to history.8

Margaret Catherine Murphy also accompanied her father into the Union ranks. Father and daughter enlisted in the 98th Ohio Volunteer Infantry at Camp Mingo near Steubenville, Ohio. Margaret’s father became the orderly sergeant of their company and looked out for his daughter. She recounted that “a few days after I enlisted, I was detected by my laugh and was suspected of being a woman. My father reported to the captain that he had examined me, and that I was a man.” Margaret served for six months, being promoted to corporal, before she irrevocably betrayed herself while drunk. Her captain ordered her into women’s clothes and sent under guard to the Wheeling jail, where she was held for three weeks under suspicion of being a rebel spy. From there she was transferred to Old Capitol Prison in Washington until she was again transferred to City Point to be exchanged.

On the exchange boat Margaret protested that she was never a rebel spy and proclaimed her love for her country and the Union, all to no avail. When it was time to turn her over to the Confederates, Margaret cursed the rebels and refused to leave the boat. Not being believed, she jumped overboard in an attempt to drown herself, but Confederates quickly fished her out. She was taken to Petersburg, where she was jailed with her hands tied behind her back. When her captors realized that she was not one of their own, Margaret was sent back north and, despite swearing her loyalty, was not believed. Again she was incarcerated in Old Capitol Prison for six months. From there she was transferred to the prison at Fitchburg, Massachusetts, where she spent the remainder of the war. Once the war ended, she was released and made her way back to Ohio.9

In 1861, Louisa Hoffman donned Union blue and served in a cavalry regiment, seeing action at both Battles of Bull Run. She left that regiment and joined the 1st Ohio Infantry Regiment as a cook. Becoming tired of that occupation and wanting to see more action, she enlisted with Battery C, 1st Tennessee Light Artillery (U.S.). She might be the only woman to have served in three branches of the Union army. In August 1864, both the Nashville Dispatch and the Washington Daily Morning Chronicle reported that “a very good-looking and respectable soldier girl,” dressed in a suit of blue with artillery trappings, made her appearance at the Nashville provost marshal’s office. She was arrested by Lieutenant Fletcher, who stated that she enlisted as a man under the name of John Hoffman, but was a woman. Upon questioning, she admitted that her real name was Louisa Hoffman and that she was from New York City. She was given female attire, escorted to Louisville, and then sent home. The tabloids added, “She makes a very handsome soldier.”10

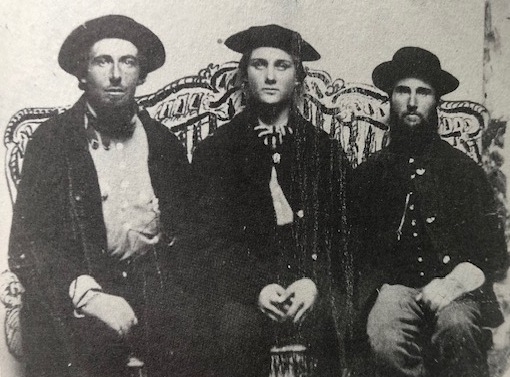

The soldier in the middle appears to be a woman.

Another non-Ohioan who served in the ranks of an Ohio regiment was Ms. Ida Bruce. She was a native of Atlanta, Georgia, and her parents were staunch Unionists. Upon the death of her parents, Ida traveled north and joined the ranks of the 7th Ohio Cavalry.11

The Nashville Dispatch reported that “A bold looking soldier girl attired in the uniform complete, was arrested in Louisville … and taken before the Provost Marshal.” Major Fitch, the provost, at first didn’t know what to do with her. She was identified as 21-year-old Elizabeth Price. She said that she had served for two years with an Ohio regiment. She donned the attire of a soldier when her lover enlisted in the army, desiring to follow and share his fortunes. She confessed that she had seen enough of the service and wanted to return home to Cincinnati. Her request was granted, and she was discharged and was soon on her way to that city.12

In August of 1861, in Lancaster, Ohio, an 18-year-old student enlisted in the 17th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Described as five feet, six inches tall, with a dark complexion, gray eyes, and black hair, Private Frank Deming was actually a woman in disguise. Deming faithfully performed all the duties of a soldier, including fighting with her regiment at the Battle of Mill Springs. In November 1861, Deming was ordered by the regimental surgeon to hospital duty. She served in that capacity for nine months until May 18, 1862 when she received a discharge for disability near Corinth, Mississippi. The discharge papers stated that Deming was “incapable of performing the duties of a soldier” because of the discovery of “a congenital peculiarity which should have prevented her admission into the Army – being a female.”13

Katie Hanson was noted prior to the war for her predilection for masculine ways. She spent a lot of time in the woods hunting and fishing in Tioga County, Pennsylvania. She was probably a tomboy and left home when her parents disapproved of the worthless boy whom she became interested in. Dressing herself in men’s clothes, she began living as a man. She found work on a Great Lakes steamboat and earned a man’s wages. When the war commenced, Katie joined an Ohio regiment. Being an expert marksman, she was soon promoted to the rank of sergeant. In 1864, after serving for three years, Sergeant Hanson’s captain confronted her with his suspicion about her gender. Catching her off guard, she confessed. Katie was discharged and sent to work as a hospital nurse. Soon after, her captain was wounded in a skirmish. Sent to the regimental hospital, he convalesced under the tender care of Katie. “Between them a strong affection was formed [and] at the close of the war they were married.”14

Marian McKenzie was a woman soldier who would not be denied from participating in the war. She enlisted at the age of 18 in the 23rd Kentucky Infantry under the name of Harry Fitzallen. After serving for eight months, she was revealed as a woman on August 27, 1862. She begged to remain in the army and was assigned as a nurse. Restless after three months, she craved more action. She left and joined the 92nd Ohio Infantry, marching with the regiment from Marietta, Ohio to Charleston, [West] Virginia. She was described as having a dark complexion, short cropped hair, coarse, rounded features, and a stocky five-foot, three-inch frame. On December 20, 1862 she was discovered as a woman and accused of being a spy. Marian was sent to the provost marshal’s office in Wheeling, where she was incarcerated. In a Wheeling paper, McKenzie was quoted, “The only way in which I violated the law is in assuming men’s apparel. The injury that I have done is principally to myself.” She added that she “went into the army for the love of excitement and from no motive in connection with the war, one way or another.” She was eventually released and promptly enlisted in the 8th Ohio Infantry, but was quickly discovered as a woman and discharged. Three strikes and she was out.15

In the summer of 1862, Mary Scaberry, a 17-year-old woman, enlisted in the 52nd Ohio Infantry under the alias of Charles Freeman. After coming down with a severe fever, she was sent first to the general hospital in Lebanon, Kentucky and on November 10 transferred to the Louisville hospital, where her identity as a woman was discovered. Mary’s discharge from the army soon followed.16

Some women, when discovered, tried to stay in the army. The few who were successful were often transferred to serve as nurses. When John Finnern returned home from his three-month enlistment with the 15th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, he decided to reenlist with the 81st Ohio Infantry. His wife Elizabeth decided that he was not leaving her again, so she signed up with him on September 23, 1861. She was discovered to be a woman, but stayed with the regiment, working as both a battlefield nurse and a surgeon’s assistant. Elizabeth was also the seamstress and laundress for the company. For practical reasons, she stayed in male attire after her gender became known. One veteran stated that Elizabeth “was on every march and battlefield with the 81st Ohio.” She was known by everyone in the regiment and “in time of danger … carried a musket just as the soldiers did, and in all respects shared the rough life of the men about her,” but with none of the benefits such as pay. She was with the regiment for the full three years and left when her husband was discharged in 1864. Elizabeth and John returned to Ohio and tried farming, but that soon failed. They moved to Indiana, where John worked as a migrant laborer until he was physically incapacitated. Elizabeth did what she could, but it was not enough. John’s pension could not support them, and the childless couple was forced to live in the Greenburg poor house. John died in 1907 and Elizabeth two years later at the age of 87.17

Fannie Lee of Cleveland, Ohio, (whose real name was Fannie E. Chamberlain) enlisted in the 6th Ohio Cavalry when she was 18 years old. She enlisted with her cousin George and saw action in Virginia in 1863-64. She became ill and instead of taking the risk of being discovered as a woman by army surgeons, went instead to the United States Sanitary Commission Hospital for treatment. Still dressed as a cavalry trooper, her gender was revealed at the hospital in Washington. When she recovered, she requested to stay in the service as a nurse, but was refused by an irate provost marshal. He said that Fannie had “so far unsex[ed] herself” as to be unworthy of a job, and she was sent home. Back in Ohio, she grew out her hair and married John H. Butts of Summit, Ohio on July 28, 1864.18

At least one officer recognized that the women soldiers were a valuable addition to the ranks. A female soldier from Cincinnati who was discovered by her commanding officer pleaded to stay in the service. The officer agreed and did not report her or have her discharged, and she remained in the ranks. When later asked why he did not dismiss her, he said, “She looks as brave as any soldier in the division. I say bully for her, and if I could get 100 of such [women] I would send a company.”19

Like Corporal Klinger (Jamie Farr from Toledo) in the TV series M*A*S*H, there was one male soldier who wanted to go home so badly that he dressed and presented himself as a woman. At City Point in January 1865, General Marsena Patrick, Provost Marshal of the Army of the Potomac, was presented with the case. “I had to examine a woman, dressed in our uniform,” Patrick wrote. “Charlie (or Charlotte) Anderson of Cleveland, Ohio, who is, or has been with the 60th Ohio … She has told me the truth, I think, about herself.” Charlie was so convincing in his disguise as a woman that Patrick sent him/her home to Ohio. Upon arrival in Cleveland, Anderson’s ruse was finally revealed upon physical examination, but it was too late. He was out of the army. As it happens, Anderson had used this ruse successfully before, probably to collect enlistment bounty. He had used the trick to leave the 38th Pennsylvania Infantry, and after enlisting in the 60th Ohio Infantry, he fooled Patrick. Anderson was successful because he was of feminine appearance. He declared, “I adopted the course I have pursued to get home … I came through City Point, I saw General Patrick … I told him I was a girl [and] he told me to go home.”20

Despite their varied reasons for disguising themselves and joining the ranks to fight in the Civil War, women soldiers went through extraordinary hardships to defend their country. The Civil War was the first time a significant number of women enlisted to fight. The women soldiers, like those from Ohio, helped to change the nation’s perception of women’s capabilities. Their front-line service proved that women should be accorded the same rights as men. These brave Buckeye women in blue paved the way for future generations of women to gain their rights and to serve in the military.

Click on the book links on this page to purchase from Amazon. Part of the proceeds from any book purchased from Amazon through the CCWRT website is returned to the CCWRT to support its education and preservation programs.

Footnotes

1. Blanton, DeAnne & Lauren M. Cook, They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War, Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 2002, p. 6. These numbers are taken from Mary A. Livermore, My Story of the War, Hartford, Connecticut, A.D. Worthington & Co., 1888, pp.119-120. Female Soldiers in the Civil War, January 25, 2013.

2. Blanton & Cook, They Fought Like Demons, pp. 42, 109. “Female Volunteer,” Cincinnati Dollar Weekly Times, August 11, 1864.

3. Blanton & Cook, They Fought Like Demons, p. 109. “Women Soldiering as Men,” New York Sun, February 10, 1901. Cairo City Weekly News, June 13, 1861. “Hid Sex in the Army,” Washington Post, January 27, 1901.

4. Peoria Morning Mail, February 14, 1863, p. 3, c. 2. Betts, Vicki, Women Soldiers, Spies, and Vivandieres: Articles from Civil War Newspapers, University of Texas at Tyler, 2016.

5. Reid, Whitlaw, ed., Ohio in the War, Vol II: The History of Her Regiments and Other Military Organizations, Cincinnati, Ohio, The Robert Clarke Company, 1895. pp. 352-355. Brooks, Rebecca Beatrice, Women Soldiers in the Civil War.

6. Blanton & Cook, They Fought Like Demons, pp. 14, 94-95. “Remarkable Incident”, Princeton (Indiana) Clarion, November 14, 1863.

7. Blanton & Cook, They Fought Like Demons, pp. 40, 65, 164-166. “Romance of an Ohio Woman,” Cleveland Leader, October 7, 1896. Soldier-Women of the American Civil War: Martha Parks Lindley.

8. Blanton & Cook, They Fought Like Demons, p. 33.

9. Blanton & Cook, They Fought Like Demons, pp. 33, 53, 121, 209. U.S. Continental Commands, part 1, entry 5812, file for Margaret Catherine Murphy, Record Group 393, National Archives. “Rebel Female Prisoners,” Worchester (Massachusetts) Aegis and Transcript, December 5, 1863.

10. Blanton & Cook, They Fought Like Demons, pp. 8, 114-115. 148. “A Woman Soldier,” Washington Daily Morning Chronicle, August 26, 1864. Nashville Dispatch, August 18, 1864, p. 2, c. 1. Betts, Vicki, Women Soldiers, Spies, and Vivandieres.

11. Blanton & Cook, They Fought Like Demons, p. 36.

12. Nashville Dispatch, March 29, 1864, p. 4, c. 2. Betts, Women Soldiers, Spies, and Vivandieres.

13. Blanton & Cook, They Fought Like Demons, pp. 10, 107. RG 94 Records of the Adjutant General’s Office (AGO) Compiled Military Service Records (CMSR), 17th Ohio Infantry, Deming, Frank.

14. Blanton & Cook, They Fought Like Demons, pp. 39, 72, 118. “Female Soldiers,” Army and Navy Register, February 11, 1882.

15. Brooks, Rebecca Beatrice, Women Soldiers in the Civil War. Soldier-Women of the American Civil War: Marian McKenzie. “Woman Arrested Serving as a Union Soldier,” Rick Steelhammer, Charleston Gazette-Mail, December 19, 2012.

16. Soldier-Women of the American Civil War: Mary Scaberry.

17. Blanton & Cook, They Fought Like Demons, pp. 30, 38, 116-117, 129, 164-166, 184. Records of the Adjutant General’s Office (AGO) Compiled Service Records, 81st Ohio Infantry, Elizabeth & John Finnern Record Group 94 National Archives. Veterans Administration Pension Application, WC 620, 476, Record Group 15, National Archives. “Women Served as Soldiers,” National Tribune, July 25, 1907.

18. Blanton & Cook. They Fought Like Demons, p. 117. Soldier-Women of the American Civil War: Fannie Lee.

19. Ibid. p. 117.

20. “A Male Woman,” Chicago Evening Journal, February 16, 1885. Patrick, Marsena, Inside Lincoln’s Army: The Diary of Marsena Rudolph Patrick, Provost Marshal General, Army of the Potomac, ed. David S. Sparks, New York & London, Thomas Yoseloff, 1964, pp. 459-460. Diary entries for January 18 & 22, 1865.